As part of a larger mission to improve public health with focus from the front lines to the front offices, the UW MHA program has made a deliberate and multi-year effort to reshape our curriculum and approach with a particular focus on health equity and effective health care administrative practices. Equity, diversity, and inclusion have become central to the work of health administration, and they are among the most pressing issues in our field today.

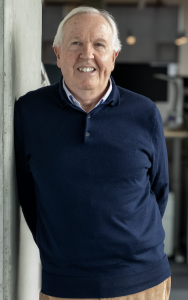

When the University of Washington’s Master of Health Administration program began enrolling its first students in the fall of 1972, health care administration was still a fledgling field of study. With the creation of Medicare in 1965, public dollars began pouring into health care, and “people were saying we have to run health care as a business as well as a service organization,” recalled UW MHA associate teaching professor Dennis Stillman. The UW MHA was among the first 15 programs in the country to train students to do just that.

The MHA program at UW was the brainchild of Dr. William Richard, who went on to head the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. His vision was for the program to draw faculty from across the university. Students, including Stillman, who enrolled in the program in 1977, studied under faculty from the schools of public health, business, architecture and urban planning, law, and engineering.

The UW MHA program is part of the School of Public Health and is dual-accredited by the Committee on the Accreditation of Health Management Education (CAHME) and the Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH).

The student becomes the teacher

Trained as an accountant, Stillman served in the Peace Corps in the early 1970s, assisting hospitals in rural Brazil with their accounting. He was instantly hooked on the challenge of applying his business acumen to tangibly improving people’s lives.

“One of the fun things about a career in health management is that you have to deal with service, quality, ethics, and finances all at the same time,” he reflected. “If I was working for a major for-profit company, the bottom line is that I make money for the owners. In health care, you have to serve the community, not just today, but 20 years from now. It makes the decisions a lot more complex, and a lot more fun to deal with.”

After completing the UW MHA in 1979, Stillman served as a CFO – first at PacMed, where he made tough decisions that enabled the organization to stay financially solvent, and then for 11 years at UW Medical Center. He returned to the MHA program in 1998 to teach a course after a faculty member stepped down, and instantly fell in love with teaching. He calls teaching a “personal gift.”

“If we are in a class, I can see when the student ‘gets it’–their posture changes, their eyes sparkle, they sit up straighter in the chair. That’s rewarding. It feels good to give back, and it’s really a way to serve the next generation,” said Stillman. “For those students, especially in the Executive MHA program who are practitioners, they can take [what they’re learning] and use it immediately. I’ve had students say to me, ‘What you just taught me, I applied right away.’”

Stillman quickly ratcheted up his teaching load, at one point, teaching 10 classes in a year. Still, he missed the excitement of running an organization, and in 2006, he established his own consulting practice. Since then, he has traveled the country, spending three to six months serving as interim CFO at organizations that have lost their CFO. The work of helping organizations in disarray has not only been fulfilling; it’s also provided a wealth of new insight to bring into the classroom. Stillman compares himself to a researcher sharing findings from their research.

Because the majority of UW’s MHA faculty have worked in the field, they stay informed of current trends and technological changes. Stillman cited the example of associate teaching professor Kurt C. O’Brien, who used his background in organizational development to coach students working at EvergreenHealth, which was ground zero for COVID-19 in the U.S.

“If I was working for a major for-profit company, the bottom line is that I make money for the owners. In health care, you have to serve the community, not just today, but 20 years from now. It makes the decisions a lot more complex, and a lot more fun to deal with.”

Preparing students for the unknown

Students are trained to tackle thorny issues, such as how to maintain employee morale during a once-in-a-generation crisis. Health care leaders must be prepared to take decisive, informed action in the face of uncertainty and ambiguity, said Stillman.

“How do you get ready for those events that you can’t plan for? How do you go through the difficult decisions of what to fund? Everyone wants their project funded, but the organization only has so much money, so how do you make the decision that’s best for the organization, and best for the community it serves? You have a responsibility to serve the community now and for decades,” said Stillman.

The UW MHA program includes courses in ethics to prepare students for these dicey situations. As technology advances, new ethical dilemmas are revealed, especially around end-of-life care. Students learn how to implement systems, such as formal ethics committees, to support the clinicians who ultimately make these fraught decisions.

UW MHA students become empowered to be change-makers, too. Graduates must navigate a seemingly rigid health care system that defaults to treating acute conditions, not preventing them, but they also have the power to shake things up. Payment systems are moving towards prevention, Stillman noted, and health systems are wrestling with how to invest in services like affordable housing and behavioral health, which are not adequately funded by government and commercial payers.

“We’ve had a lot of leaders in Northwestern health care come through this program, so it’s really helped form a lot of the organizations and the values that have driven health care in the Northwest,” reflected Stillman.

UW MHA alums introduced Toyota Production to U.S. health care at Virginia Mason Medical Center. They served as the CEO of GroupHealth cooperative, an innovator in preventive health care, and steered the Washington State Health Care Authority during the implementation of the Affordable Care Act.

Effective leadership

In the nearly 50 years he’s been involved with the University of Washington’s Master of Health Administration program, Stillman has gleaned the recipe for an effective leader. He implores his students to “learn the rules in order to move the rules.”

“You have to be idealistic to follow a career in health administration. You must enjoy leading change, working with intelligent, driven health care professionals. Our program teaches our students to drive change, work in multidisciplinary teams, and serve their communities. I enjoy my career and it’s not over yet.”