HSPop faculty member Stephen Bezruchka connects the dots between population health, attention to health in early life, economic inequality and life expectancy.

Dr. Stephen Bezruchka began his medical career as an emergency physician, after stints in Nepal setting up community health projects. He earned his MPH at John Hopkins in the ’80s, at a time when the idea of social determinants of health was gaining traction. He changed his focus from treating patients to treating populations, as he likes to say.

“Economic inequality, together with the attention to [health in] early life, are the two major factors that determine the health of a population. By the time you’ve blown out two candles on your second birthday cake, roughly half of your health as an adult has been programmed.”

-Dr. Stephen Bezruchka

“I thought medical care and personal behaviors were what really mattered. And then I came to realize that for child survival in developing countries, whether or not the mother was educated mattered more than medical care. These were ideas circulating in the 1980’s that social circumstances really mattered for health. I wasn’t taught that in medical school, it was all [about] treating illness and injury,” said Dr. Bezruchka.

“Then I began to realize that mortality rates or lifespan was not very high in the United States. Like so many Americans, I assumed we were the best at everything, and I came to realize that our status when measured by mortality outcomes in health was not very good. In fact, they were kind of shameful. I began to wonder what really produced health in a population.”

Bringing it into the classroom

Fast-forward to the present, and Dr. Bezruchka teaches a class, HSPoP 482: The Health Of Populations, that replicates those “ah-ha” moments for a new generation. The course tackles health around the world, using the U.S., Cuba, Haiti, and Japan (which has the highest life expectancy globally) as case studies.

Bezruchka notes that 43 countries have a higher life expectancy than the U.S., including all of our rich peers, as well as some developing countries like Sri Lanka. The class also delves into change over time, including in Russia, where life expectancy plummeted after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Every assignment is designed to stretch students’ thinking and promote active learning. In one particularly popular activity, students are given cards representing 16 countries and are asked to rank them by some measure, such as money spent on healthcare or child mortality. Later, they research the real ranking, and give a presentation comparing the real and perceived rankings. Students are often bewildered to discover how low the U.S. ranks on certain key measures, said Dr. Bezruchka.

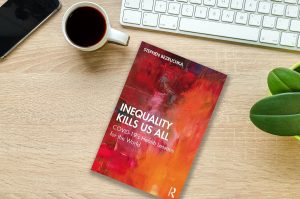

As a textbook, he uses the book he published in 2022, Inequality Kills Us All: COVID-19’s Health Lessons for the World. He presents evidence that increasing inequality is to blame for the U.S. losing its spot as one of the healthiest countries in the world in the ’50s. For example, inequality foments unrest and social divisions that scholars have linked to increases in mass shootings.

Dr. Bezruchka worries that the media neglects to consider structural violence, or the social inequities that lead to loss of life. He has a prescription, however: redistributing wealth into evidence-backed programs to boost early childhood health.

“Economic inequality, together with the attention to [health in] early life, are the two major factors that determine the health of a population,” he explained. “By the time you’ve blown out two candles on your second birthday cake, roughly half of your health as an adult has been programmed. As one of my students put it some years ago, ‘Early life lasts a lifetime.’ Policies can privilege early life, and one way to do that is to give a working woman who’s pregnant time off after she has her baby. Only two countries in the world do not have a national [paid maternity leave] policy. One is, of course, the United States, and the other is Papua New Guinea.”

Since Inequality Kills Us All was published, new CDC data shows an uptick in life expectancy since the pandemic, although it still hasn’t rebounded to pre-pandemic levels. Undoubtedly, COVID-19 sent shockwaves across our health system that continue to be felt.Bezruchka’s new book, titled Born Sick in the USA, focuses on disease risk and is scheduled to be published by Cambridge University Press next year. Until then, he’ll continue challenging students to question what really causes adverse health outcomes.